Western microchips used to power smartphones and laptops are continuing to enter Russia and fuel its military arsenal, new analysis shows.

Trade data and manifests analyzed by CNBC show that Moscow has been sourcing an increased number of semiconductors and other advanced Western technologies through intermediary countries such as China.

In 2022, Russia imported $2.5 billion worth of semiconductor technologies, up from $1.8 billion in 2021.

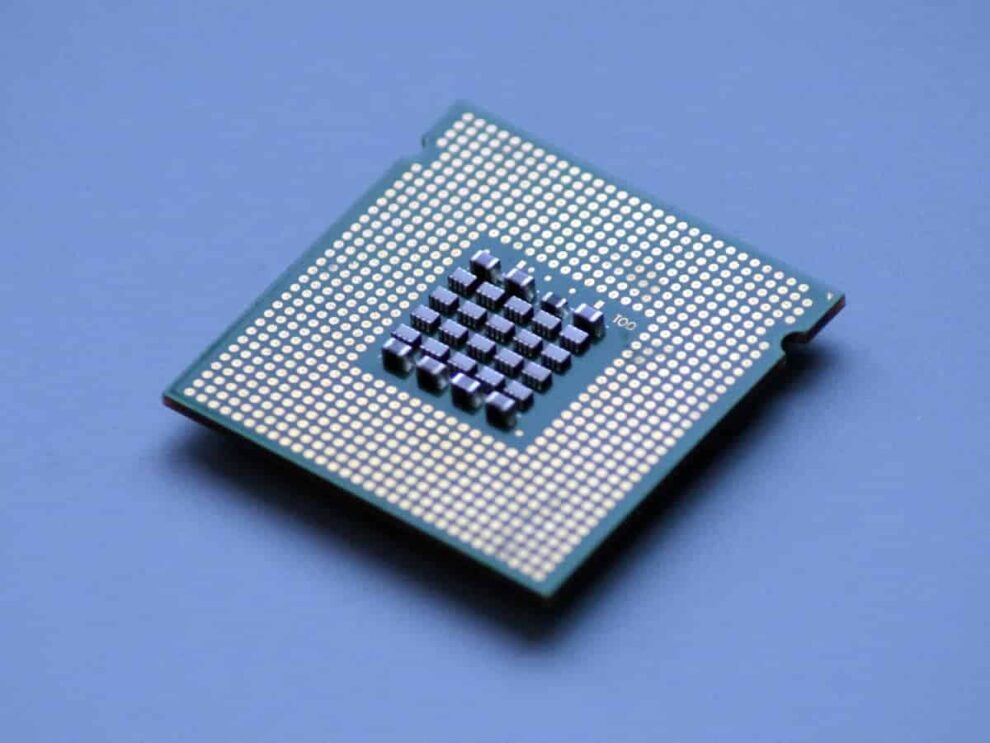

Semiconductors and microchips play a crucial role in modern-day warfare, powering a range of equipment including drones, radios, missiles and armored vehicles.

Indeed, the KSE Institute — an analytical center at the Kyiv School of Economics — recently analyzed 58 pieces of critical Russian military equipment recovered from Ukraine’s battlefield and found more than 1,000 foreign components, primarily Western semiconductor technologies.

Many of these components are subject to export controls. But, according to analysts CNBC spoke to, convoluted trade routes via China, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and elsewhere mean they are still entering Russia, adding to the country’s prewar stockpiles.

A collection of 58 pieces of Russian weaponry captured from the battlefield in Ukraine, such and drones and missiles, contained more than 1,000 Western components, according to a study from the KSE Institute.

“Russia is still being able to import all the necessary Western-produced critical components for its military,” said Elina Ribakova, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, and one of the authors of KSE Institute’s report.

“The sanctions evasion and avoidance is surprisingly brazen at the moment,” she added.

Murky supply chains

Not all advanced technologies are subject to Western sanctions on Russia.

Many are dubbed dual-use items, meaning they have both civilian and military applications, and therefore fall outside of the scope of targeted export controls. A microchip may have applications in both a washing machine and a drone, for instance.

Still, many of these products originate from Western nations with sweeping trade bans against Moscow and, specifically, its military. All U.S.-origin items except food and medicine are prohibited from reaching Russia’s army.

In KSE’s study, more than two-thirds of the foreign components identified in Russian military equipment ultimately originated from companies headquartered in the U.S., with others coming from Ukrainian allies including Japan and Germany.

CNBC was unable to verify whether the implicated companies were aware of the final destination of their goods. Swiss authorities said they were working with firms to “educate them on red flags,” while government spokespeople for the other countries cited did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Separately, a study from the Royal United Services Institute found that Russia’s military uses over 450 different types of foreign-made components in its 27 most modern military systems, including cruise missiles, communications systems and electronic warfare complexes. Many of these parts are made by well-known U.S. companies that create microelectronics for the U.S. military.

More than two-thirds of tech elements recovered in KSE Institute’s study originated from companies headquartered in the U.S.

“Over decades, non-Russian high-tech systems and technologies became more advanced and really have become industry and global standards. So, a Russian military, as well as its civilian economy, have become dependent,” Sam Bendett, advisor at the Center for Naval Analyses, said.

The ubiquity and wide-reaching applications of such technologies have led them to become intertwined in global supply chains and therefore harder to police. Meanwhile, sanctions on Russia are largely limited to Ukraine’s Western allies, meaning that many countries continue to trade with Russia.

“It’s difficult to stop strictly civilian microelectronics from crossing borders and from taking place in global trade. And this is what the Russian industry as well as the Russian military and its intelligence services are taking advantage of,” Bendett said.

Russia-China trade spikes

Those trade flows can be messy. Typically, a shipment may be sold and resold several times, often through legitimate businesses, before eventually reaching a neutral intermediary country, where it can then be sold to Russia.

Data suggests China is by far the largest exporter to Russia of microchips and other technology found in crucial battlefield items.

Sellers from China, including Hong Kong, accounted for more than 87% of total Russian semiconductor imports in the fourth quarter of 2022, compared with 33% in Q4 2021. More than half (55%) of those goods were not manufactured in China, but instead produced elsewhere and shipped to Russia via China and Hong Kong-based intermediaries.

“This should not be taken as a surprise because China is really trying to accumulate and to make profits and gains on the fact that Russia is economically isolated,” Olena Yurchenko, advisor at the Economic Security Council of Ukraine, said.

China’s trade department did not respond to a request for comment on the findings, nor did the Russian government.

Meantime, Moscow has also increased its imports from so-called intermediary countries in the Caucasus, Central Asia and the Middle East, according to national trade data.

Exports to Russia from Central Asia and Caucasus countries has increased significantly since Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, trade data shows.

Exports to Russia from Georgia, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, for instance, surged in 2022, with vehicles, aircraft and vessels accounting for a significant share of the uptick. At the same time, European Union and U.K. exports to those countries rose, while their direct trade with Russia plunged.

“A lot of these countries really cannot sever certain types of trade with Russia, especially those nations which are either bordering Russia, like Georgia, for example … as well as nations in Central Asia, which maintain a very significant trade balance with the Russian Federation,” Bendett said.

The governments of Georgia, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan did not respond to CNBC’s request for comment on the increase in trade.

Sanctions clampdown

The burgeoning trade flows have prompted calls from Western allies to either get more countries on board with sanctions, or slap secondary sanctions on certain entities operating within those countries in a bid to stifle Russia’s military strength.

In June 2023, the European Union adopted a new package of sanctions which includes an anti-circumvention tool to restrict the “sale, supply, transfer or export” of specified sanctioned goods and technology to certain third countries acting as intermediaries for Russia.

The package also added 87 new companies in countries spanning China, the United Arab Emirates and Armenia to the list of those directly supporting Russia’s military, and restricted the export of 15 technological items found in Russian military equipment in Ukraine.

“We are not sanctioning these countries themselves. What we are doing is preventing an already sanctioned product, which should not reach Russia, from reaching Russia through a third country,” EU spokesperson Daniel Ferrie said.

However, some are skeptical that the measures go far enough — particularly when it comes to major global trade partners.

″[The sanctions] may work against, let’s say, Armenia or Georgia, which are not big trade partners for European Union or for the United States. But in when it comes, for instance, to China or to Turkey, that’s a very unlikely scenario,” Yurchenko, of the Economic Security Council of Ukraine, said.

Others say that responsibility ultimately lies with the companies, which need to do more to monitor their supply chains and avoid their goods falling into the wrong hands.

“The companies themselves should have the infrastructure to be able to track it and comply with export controls,” Ribakova said.

“If we have certain moral values or national security objectives, we cannot be giving [to Ukraine] with one hand and then giving to Russia with the other.”

Source : CNBC